| |

|

| |

In March 1861

British explorer Samuel White Baker (8 June 1821 – 30

December 1893) started upon his first tour of exploration

in central Africa. This, in his own words, was undertaken

"to discover the sources of the river Nile, with the

hope of meeting the East African expedition under Captains

Speke and Grant somewhere about the Lake Victoria." After

a year spent on the Sudan–Ethiopian frontier, during

which time he learned Arabic, explored the Atbara river and

other Nile tributaries, and proved that the Nile sediment

came from Ethiopia, he arrived at Khartoum, leaving that city

in December 1862 to follow up the course of the White Nile.

Two months later at Gondokoro he met fellow

British explorers Speke and Grant, who, after discovering

the source of the Nile, were following the river to Egypt.

Their success made him fear that there was nothing left

for his own expedition to accomplish; but the two explorers

gave him information which enabled him, after separating

from them, to achieve the discovery of Albert Nyanza (Lake

Albert), of whose existence credible assurance had already

been given to Speke and Grant. Baker first sighted the lake

on March 14, 1864. After some time spent in the exploration

of the neighbourhood, Baker demonstrated that the Nile flowed

through the Albert Nyanza. He formed an exaggerated idea

of the relative importance of the Albert and Victoria lake

sources in contributing to the Nile flow rate. Although

he believed them to be near equal, Albert Nyanza sources

add only ~15% to the Nile flow at this point, the remainder

provided primarily by outflow from Lake Victoria. He started

upon his return journey, and reached Khartoum, after many

checks, in May 1865.

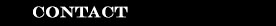

In

the following October Baker returned to England with his

wife, who had accompanied him throughout the dangerous and

difficult journeys in Africa. In recognition of the achievements,

the Royal Geographical Society awarded him its gold medal,

and a similar distinction was bestowed on him by the Paris

Geographical Society.

|

| |

|

|

|

Sir

Samuel White Baker KCB, FRS, FRGS and his wife Florence

von Sass (Lady Baker) as illustrated in the London

News approx. 1873 |

|

In

August 1866 he was knighted. In the same year he published

The Albert N'yanza, Great Basin of the Nile, and Explorations

of the Nile Sources, and in 1867 The Nile Tributaries of Abyssinia,

both books quickly turned into several editions. In 1868 he

published a popular story called Cast up by the Sea. In 1869

he travelled with the future King Edward VII (who was the

Prince of Wales at that time) through Egypt.

Baker never received quite the same level of acclamation

granted to other contemporary British explorers of Africa.

Queen Victoria, in particular, avoided meeting Baker because

of the irregular way in which he acquired Florence, not

to mention the fact that during the years of their mutual

travels, the couple were not actually married.

|

| |

|

|

|

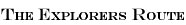

Isma'il

Pasha with attendants circa 1855 |

|

A court case involving his brother Valentine Baker (following

his indecent assault of a woman on a train) also harmed Baker's

chances of wider acceptance by the Victorian establishment.

Baker led a military expedition to the equatorial regions

of the Nile, with the object of suppressing the slave-trade

there and opening the way to commerce and civilization.

Before starting from Cairo with a force of 1700 Egyptian

troops - many of them discharged convicts - he was given

the rank of pasha and major-general in the Ottoman army.

Lady Baker, as before, accompanied him. The khedive appointed

him Governor-General of the new territory of Equatoria for

four years at a salary of £10,000 a year; and it was

not until the expiration of that time that Baker returned

to Cairo, leaving his work to be carried on by the new governor,

Colonel Charles George Gordon.

He had to contend with innumerable difficulties - the blocking

of the river in the Sudd, the hostility of officials interested

in the slave-trade, the armed opposition of the natives

- but he succeeded in planting in the new territory the

foundations upon which others could build up an administration.

|

|

| |

|

| |

Nubia

The name Nubia is derived from that of the Noba people,

nomads who settled the area in the 4th century, with the

collapse of the kingdom of Meroë. The Noba spoke a

Nilo-Saharan language, ancestral to Old Nubian. Old Nubian

was used in mostly religious texts dating from the 8th and

15th centuries AD. Before the 4th century, and throughout

classical antiquity, Nubia was known as Kush, or, in Classical

Greek usage, included under the name Ethiopia (Aithiopia).

There were a number of small Nubian kingdoms throughout

the Middle Ages, the last of which collapsed in 1504, when

Nubia became divided between Egypt and the Sennar sultanate

resulting in the Arabization of much of the Nubian population.

Nubia was again united within Ottoman Egypt in the 19th

century, and within Anglo-Egyptian Sudan from 1899 to 1956.

Historically, the people of Nubia spoke at least two varieties

of the Nubian language group, a subfamily which includes

Nobiin (the descendant of Old Nubian), Kenuzi-Dongola, Midob

and several related varieties in the northern part of the

Nuba Mountains in South Kordofan. A variety (Birgid) was

spoken (at least until 1970) north of Nyala in Darfur but

is now extinct.

Throughout the world, Nubia is broken into three unique

regions: “Lower Nubia”, "Upper Nubia",

and "Southern Nubia." "Lower Nubia"

was in modern southern Egypt, which lies between the first

and second cataract. “Upper Nubia and Southern Nubia"

were in modern-day northern Sudan, between the second cataract

and sixth cataracts of the Nile river. Lower Nubia and Upper

Nubia are so called because the Nile flows north, so Upper

Nubia was further upstream and of higher elevation, even

though it lies geographically south of Lower Nubia.

|

|

Nubia and Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt conquered Nubian territory in various eras,

and incorporated parts of the area into its provinces. The

Nubians in turn were to conquer Egypt under its 25th Dynasty.

Relations between the two peoples however also show peaceful

cultural interchange and cooperation, including mixed marriages.

The Medjay –from mDA, represents the name Ancient

Egyptians gave to a region in northern Sudan–where

an ancient people of Nubia inhabited. They became part of

the Ancient Egyptian military as scouts and minor workers.

During the Middle Kingdom "Medjay" no longer

referred to the district of Medja, but to a tribe or clan

of people. It is not known what happened to the district,

but, after the First Intermediate Period, it and other districts

in Nubia were no longer mentioned in the written record.

Written accounts detail the Medjay as nomadic desert people.

Over time they were incorporated into the Egyptian army.

In the army, the Medjay served as garrison troops in Egyptian

fortifications in Nubia and patrolled the deserts as a kind

of gendarmerie. This was done in the hopes of preventing

their fellow Medjay tribespeople from further attacking

Egyptian assets in the region. They were even later used

during Kamose’s campaign against the Hyksos and became

instrumental in making the Egyptian state into a military

power. By the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom period the

Medjay were an elite paramilitary police force. No longer

did the term refer to an ethnic group and over time the

new meaning became synonymous with the policing occupation

in general. Being an elite police force, the Medjay were

often used to protect valuable areas, especially royal and

religious complexes. Though they are most notable for their

protection of the royal palaces and tombs in Thebes and

the surrounding areas, the Medjay were known to have been

used throughout Upper and Lower Egypt.

|

| |

|

Various pharaohs of Nubian origin are held

by some Egyptologists to have played an important part towards

the area in different eras of Egyptian history, particularly

the 12th Dynasty. These rulers handled matters in typical

Egyptian fashion, reflecting the close cultural influences

between the two regions.

...the XIIth Dynasty (1991–1786 B.C.E.) originated

from the Aswan region. As expected, strong Nubian features

and dark coloring are seen in their sculpture and relief

work. This dynasty ranks as among the greatest, whose fame

far outlived its actual tenure on the throne. Especially

interesting, it was a member of this dynasty that decreed

that no Nehsy (riverine Nubian of the principality of Kush),

except such as came for trade or diplomatic reasons, should

pass by the Egyptian fortress and cops at the southern end

of the Second Nile Cataract. Why would this royal family

of Nubian ancestry ban other Nubians from coming into Egyptian

territory? Because the Egyptian rulers of Nubian ancestry

had become Egyptians culturally; as pharaohs, they exhibited

typical Egyptian attitudes and adopted typical Egyptian

policies. (Yurco 1989)

In the New Kingdom, Nubians and Egyptians were often so

closely related that some scholars consider them virtually

indistinguishable, as the two cultures melded and mixed

together.

It is an extremely difficult task to attempt to describe

the Nubians during the course of Egypt's New Kingdom, because

their presence appears to have virtually evaporated from

the archaeological record. The result has been described

as a wholesale Nubian assimilation into Egyptian society.

This assimilation was so complete that it masked all Nubian

ethnic identities insofar as archaeological remains are

concerned beneath the impenetrable veneer of Egypt's material

culture. In the Kushite Period, when Nubians ruled as Pharaohs

in their own right, the material culture of Dynasty XXV

(about 750–655 B.C.E.) was decidedly Egyptian in character.

Nubia's entire landscape up to the region of the Third Cataract

was dotted with temples indistinguishable in style and decoration

from contemporary temples erected in Egypt. The same observation

obtains for the smaller number of typically Egyptian tombs

in which these elite Nubian princes were interred.

|

| |

|

|

|

click

for larger view |

|

Kingdom of Kerma

The Turin Papyrus MapFrom the pre-Kerma culture, the first

kingdom to unify much of the region arose. The Kingdom of

Kerma, named for its presumed capital at Kerma, was one of

the earliest urban centers in the Nile region. By 1750 BC,

the kings of Kerma were powerful enough to organize the labor

for monumental walls and structures of mud brick. They also

had rich tombs with possessions for the afterlife and large

human sacrifices. George Reisner excavated sites at Kerma

and found large tombs and a palace-like structures. The structures,

named (Deffufa), alluded to the early stability in the region.

At one point, Kerma came very close to conquering Egypt. Egypt

suffered a serious defeat at the hands of the Kushites. According

to Davies, head of the joint British Museum and Egyptian archaeological

team, the attack was so devastating that if the Kerma forces

chose to stay and occupy Egypt, they might have eliminated

it for good and brought the great nation to extinction. When

Egyptian power revived under the New Kingdom (c. 1532–1070

BC) they began to expand further southwards. The Egyptians

destroyed Kerma's kingdom and capitol and expanded the Egyptian

empire to the Fourth Cataract. By the end of the reign of

Thutmose I (1520 BC), all of northern Nubia had been annexed.

The Egyptians built a new administrative center at Napata,

and used the area to produce gold. The Nubian gold production

made Egypt a prime source of the precious metal in the Middle

East. The primitive working conditions for the slaves are

recorded by Diodorus Siculus who saw some of the mines at

a later time. One of the oldest maps known is of a gold mine

in Nubia, the Turin Papyrus Map dating to about 1160 BC.

|

| |

|

|

| |

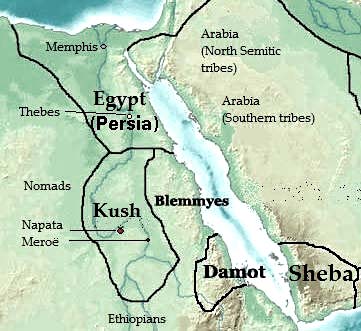

The area

around 400 B.C. |

Kingdom

of Kush

Nubian PharaohsWhen the Egyptians pulled out of the

Napata region, they left a lasting legacy that was merged

with indigenous customs forming the kingdom of Kush.

Archaeologists have found several burials in the area

which seem to belong to local leaders. The Kushites

were buried there soon after the Egyptians decolonized

the Nubian frontier. Kush adopted many Egyptian practices,

such as their religion. The Kingdom of Kush survived

longer than that of Egypt, invaded Egypt (under the

leadership of king Piye), and controlled Egypt during

the 8th century, Kushite dynasty. The Kushites held

sway over their northern neighbors for nearly 100 years,

until they were eventually repelled by the invading

Assyrians. The Assyrians forced them to move farther

south, where they eventually established their capital

at Meroë. Of the Nubian kings of this era, Taharqa

is perhaps the best known. Taharqa, a son and the third

successor of King Piye, was crowned king in Memphis

in c.690. Taharqa ruled over both Nubia and Egypt, restored

Egyptian temples at Karnak, built new temples and pyramids

in Nubia, and repelled some Assyrian attacks. |

|

|

| |

|

|

The

pyramids at Meroë |

|

| |

|

Meroë

Meroë (800 BC – c. AD 350) in southern Nubia lay

on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km north-east of the

Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, ca. 200 km north-east

of Khartoum. The people there preserved many ancient Egyptian

customs but were unique in many respects. They developed their

own form of writing, first utilizing Egyptian hieroglyphs,

and later using an alphabetic script with 23 signs. Many pyramids

were built in Meroë during this period and the kingdom

consisted of an impressive standing military force. Strabo

also describes a clash with the Romans in which the Romans

were defeated by Nubian archers under the leadership of a

"one-eyed" (blind in one eye) queen. During this

time, the different parts of the region divided into smaller

groups with individual leaders, or generals, each commanding

small armies of mercenaries. They fought for control of what

is now Nubia and its surrounding territories, leaving the

entire region weak and vulnerable to attack. Meroë would

eventually meet defeat by a new rising kingdom to their south,

Aksum, under King Ezana.

The classification of the Meroitic language is uncertain,

it was long assumed to have been of the Afro-Asiatic group,

but is now considered to have likely been an Eastern Sudanic

language. At some point during the 4th century, the region

was conquered by the Noba people, from which the name Nubia

may derive (another possibility is that it comes from Nub,

the Egyptian word for gold). From then on, the Romans referred

to the area as the Nobatae.

Christian Nubia: Makuria, Nobadia,

and Alodia

Around AD 350 the area was invaded by the Ethiopian kingdom

of Aksum and the kingdom collapsed. Eventually three smaller

kingdoms replaced it: northernmost was Nobatia between the

first and second cataract of the Nile River, with its capital

at Pachoras (modern day Faras); in the middle was Makuria,

with its capital at Old Dongola; and southernmost was Alodia,

with its capital at Soba (near Khartoum). King Silky of

Nobatia crushed the Blemmyes, and recorded his victory in

a Greek inscription carved in the wall of the temple of

Talmis (modern Kalabsha) around AD 500.

While bishop Athanasius of Alexandria consecrated one Marcus

as bishop of Philae before his death in 373, showing that

Christianity had penetrated the region by the 4th century,

John of Ephesus records that a Monophysite priest named

Julian converted the king and his nobles of Nobatia around

545. John of Ephesus also writes that the kingdom of Alodia

was converted around 569. However, John of Biclarum records

that the kingdom of Makuria was converted to Catholicism

the same year, suggesting that John of Ephesus might be

mistaken. Further doubt is cast on John's testimony by an

entry in the chronicle of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of

Alexandria Eutychius, which states that in 719 the church

of Nubia transferred its allegiance from the Greek to the

Coptic Church.

|

| |

|

By the 7th century Makuria expanded becoming the dominant

power in the region. It was strong enough to halt the southern

expansion of Islam after the Arabs had taken Egypt. After

several failed invasions the new rulers agreed to a treaty

with Dongola allowing for peaceful coexistence and trade.

This treaty held for six hundred years. Over time the influx

of Arab traders introduced Islam to Nubia and it gradually

supplanted Christianity. While there are records of a bishop

at Qasr Ibrim in 1372, his see had come to include that located

at Faras. It is also clear that the cathedral of Dongola had

been converted to a mosque in 1317.

The influx of Arabs and Nubians to Egypt and Sudan had

contributed to the suppression of the Nubian identity following

the collapse of the last Nubian kingdom around 1504. A major

part of the modern Nubian population became totally Arabized

and some claimed to be Arabs (Jaa'leen – the majority

of Northern Sudanese – and some Donglawes in Sudan).

A vast majority of the Nubian population is currently Muslim,

and the Arabic language is their main medium of communication

in addition to their indigenous old Nubian language. The

unique characteristic of Nubian is shown in their culture

(dress, dances, traditions, and music).

Islamic Nubia

In the 14th century the Dongolan government collapsed and

the region became divided and dominated by Arabs. The next

centuries would see several Arab invasions of the region,

as well as the establishment of a number of smaller kingdoms.

Northern Nubia was brought under Egyptian control while

the south came under the control of the Kingdom of Sennar

in the 16th century. The entire region would come under

Egyptian control during the rule of Mehemet Ali in the early

19th century, and later became a joint Anglo-Egyptian condominium.

|

| |

|

| |

| |

|